The Chinese Confession Program / 1956-65

The Chinese Confession Program was a program run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in the United States between 1956 and 1965, that sought confessions of illegal entry from US citizens and residents of Chinese origin, with the (somewhat misleading) offer of legalization of status in exchange. It was an important component of U.S. immigration policy toward the People's Republic of China In 1882, the U.S. made Chinese people its first targets of enforced immigration restriction. As a result, most who immigrated during the period of “Chinese exclusion” did so through a complex system of faked documentation. When FDR repealed those the laws in 1943 he called them “a historic mistake,” but most Chinese Americans continued living in the shadow of their false identities, vulnerable to discovery and deportation. Read More on Wikipedia

Emmett Till’s Murder / Aug. 28, 1955

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941 – August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted, tortured and lynched in Mississippi in 1955, after being accused of offending a white woman in her family's grocery store. The brutality of his murder and the fact that his killers were acquitted drew attention to the long history of violent persecution of African Americans in the United States. Till posthumously became an icon of the civil rights movement. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to display his lifeless body to be photographed in an open casket for the world to see, it was the catalyst that set the civil rights movement in motion. In September 1955, an all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty of Till's murder. Protected against double jeopardy, the two men publicly admitted in a 1956 interview with Look magazine that they had tortured and murdered the boy, selling the story of how they did it for $4000.[6] In 2017, author Timothy Tyson released details of a 2008 interview with Carolyn Bryant. He claimed that during the interview she had disclosed that she had fabricated parts of her testimony at the trial.[130][42][131] Tyson said that during the interview, Bryant retracted her testimony that Till had grabbed her around her waist and uttered obscenities, saying "that part's not true".[132][133]

The Wilmington Insurrection / Nov. 10, 1898

The Wilmington insurrection of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898 or the Wilmington coup of 1898,[6] was a riot and insurrection carried out by white supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina, United States, on Thursday, November 10, 1898.[7] In 1898, Wilmington, N.C., saw the only instance in U.S. history in which a legitimate government was overthrown by a white-supremacist coup. Newspapers stroked white citizens’ fears and, despite numerous warnings, the federal government left Blacks in Wilmington to defend themselves. On Election Day, the white supremacists retook the government by force, made all Black politicians resign and declared a White Declaration of Independence. Black newspapers all over the state were also being destroyed. In addition, blacks, along with white Republicans, were denied entrance to city centers throughout the state.[11]

Smallpox Outbreak in the West / 1779

At the same time that the American Revolution was raging in the East, a smallpox pandemic occurred in the West that affected the course of American history. Breaking out in Mexico City in 1779, it reached New Mexico and then spread along the networks by which horses had dispersed northward, devastating thriving and wealthy Native American tribes as it traveled along the Columbia River to the northwest coast and across Canada to the shores of the Hudson Bay. The death tolls were staggering. This massive outbreak occurred in a region that was not yet “American,” but American history has always been shaped by events beyond the borders of the U.S. This event is a reminder that, even today, power and prosperity cannot guarantee immunity to disaster, and the heartland of America cannot escape the impact of developments thousands of miles away.

The Sand Creek Massacre / Nov. 29, 1864

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of the Third Colorado Cavalry[5] under the command of U.S. Volunteers Colonel John Chivington attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people in southeastern Colorado Territory,[6] killing and mutilating an estimated 69 to over 600 Native American people. Chivington claimed 500 to 600 warriors were killed. However, most sources estimate around 150 people were killed, about two-thirds of whom were women and children.[4][2][7][3] The massacre is considered part of a series of events known as the Colorado War. On Nov. 29, 1864, a regiment of Colorado volunteer cavalrymen attacked an encampment of Cheyenne and Arapahos at Sand Creek, 180 miles southeast of Denver, killing about 200 people, mostly women and children. John Chivington, the pistol-packing minister who led the assault, described it as a glorious Union victory against “red rebels” who had sided with the Confederacy. But rumors of atrocities soon surfaced and led to congressional inquiries that cast the raid as a shameful slaughter of pacified Indians. Captain Silas Soule testified that troops shot, scalped and mutilated noncombatants. Two months later he was murdered in Denver.

The Comstock Act / March 3, 1873

The Comstock Laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.[1] The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use. This Act criminalized any use of the U.S. Postal Service to send any of the following items:[2] obscenity, contraceptives, abortifacients, sex toys, personal letters with any sexual content or information, or any information regarding the above items. Anthony Comstock was a dry-goods salesman from Connecticut who made combating sex in print his life’s work. He tirelessly lobbied until Congress in 1873 passed “an Act for the Suppression of Trade in and Circulation of Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use.” The most common such “literature,” however, was not pornography but advertisements for contraception. As the 19th century progressed, women—especially native-born, white, middle-class women—had decided to limit their fertility. In 1800, the average Protestant white women had seven or eight children; by 1900, she had 3.5. Comstock and other elite men were aghast, mainly at the idea that immigrants might out-populate white Protestants. The Comstock Act made information about birth control almost impossible to find.

The Santa Barbara Oil Spill / Jan. 28, 1969

On Jan. 28, 1969, a Union Oil rig off Santa Barbara, Calif., suffered a blowout. Three million barrels of crude eventually blanketed 35 miles of coastline. An estimated 3,500 sea birds and countless marine animals, smothered by sticky goo, perished; images of their suffering seared the nation. Among the reporters and politicians who anxiously surveyed the carnage was President Richard Nixon, who translated what he’d seen into bipartisan policies including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. In his 1970 State of the Union address, he acknowledged that the “question of the ’70s” was whether Americans could “make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water.” He could see that if we didn’t make that peace, we’d have to live with the ugly consequences. Fifty years later, at a moment when a different Republican president seeks to roll back environmental protections, including those regulating offshore oil drilling, Nixon’s exhortation is more urgent than ever.

Read TIME’s original coverage of the oil spill, in the TIME Vault

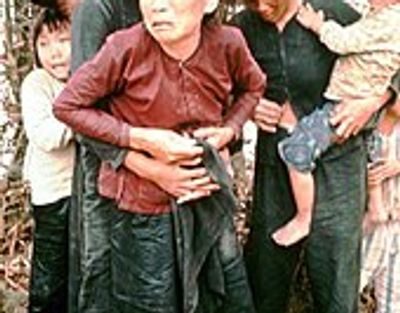

The My Lai massacre / March 16, 1968

On March 16, 1968, U.S. Army soldiers in Charlie Company killed as many as 567 South Vietnamese civilians, including women and children, in what became known as the My Lai Massacre. When the public learned about the massacre in November 1969, with harrowing photographs of dead villagers on major American television networks and in newsweeklies including TIME, it created a firestorm of controversy. Ultimately, however, the perpetrators were never held accountable. The platoon commander Lieutenant William Calley Jr. was initially given a life sentence but, at the order of President Nixon, was put under house arrest instead. He was released three and a half years later. Twenty-six soldiers were charged in military courts but none were convicted. My Lai offers a tragic cautionary tale about what can happen if a nation’s leaders choose to look the other way when racism trumps decency.

Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast Program Attacks / 1969

The Free Breakfast for School Children Program was a community service program run by the Black Panther Party that focused on providing free breakfast for children before school. The program began in January 1969 at Father Earl A. Neil's St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, located in West Oakland, California[1] and spread throughout the nation. In 1969, the Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast for Children Program fed tens of thousands of hungry kids in cities across the U.S. But, fearing the Panthers’ growing popularity, the FBI and local police tried to stamp the program out. In Baltimore, police raided the breakfast with guns drawn. In Chicago, police broke into the church that hosted the breakfast at night and smashed and urinated on the food. In Harlem, the police started rumors that the food was poisoned.The FBI won the battle in some places because parents became afraid to send their kids to the breakfast. In other places, the tactic backfired as the community claimed the Panthers as their own. In future years, the Panthers renamed and expanded their community-based “survival programs” and, ironically, the USDA used the Breakfast Program as a model for a federal school breakfast program.

Virginia’s Act XII / 1662

In December of 1662, the men who comprised Virginia’s General Assembly decided to resolve what they saw as a growing problem in the colony. Englishmen were having children with African-descended women, both free and enslaved. Some English fathers enslaved those children, but others treated their mixed-race children like free persons. While their decisions to free their children were consistent with English law, free mixed-race children blurred the racial divide forming in Virginia by the 1660s. In the eyes of the General Assembly, this inconsistency could not stand.To fix the problem, they implemented Act XII, which declared that “Negro women’s children [were] to serve according to the condition of the[ir] mother[s]”— in direct contrast with paternal descent laws that prevailed in England. This law made enslavement a heritable condition and was instrumental in the formation of a racially divided society in which African descent signified bondage. It also financially incentivized acts of sexual violence against enslaved women.

The Arab oil embargo / Oct. 20, 1973

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries led by Saudi Arabia proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War.[1] The initial nations targeted were Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States with the embargo also later extended to Portugal, Rhodesia and South Africa. By the end of the embargo in March 1974,[2] the price of oil had risen nearly 300%, from US$3 per barrel ($19/m3) to nearly $12 per barrel ($75/m3) globally; US prices were significantly higher. The embargo caused an oil crisis, or "shock", with many short- and long-term effects on global politics and the global economy.[3] It was later called the "first oil shock", followed by the 1979 oil crisis, termed the "second oil shock".

Read TIME’s original coverage of the embargo, in the TIME Vault

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire / 1911

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, on Saturday, March 25, 1911, was the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of the city, and one of the deadliest in U.S. history.[1] The fire caused the deaths of 146 garment workers – 123 women and girls and 23 men[2] – who died from the fire, smoke inhalation, or falling or jumping to their deaths. Most of the victims were recent Italian or Jewish immigrant women and girls aged 14 to 23;[3][4] of the victims whose ages are known, the oldest victim was 43-year-old Providenza Panno, and the youngest were 14-year-olds Kate Leone and Rosaria "Sara" Maltese.[5] Because the doors to the stairwells and exits were locked[1][8] – a common practice at the time to prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks and to reduce theft[9] – many of the workers could not escape from the burning building and jumped from the high windows. The fire led to legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), which fought for better working conditions for sweatshop workers.

Read more about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, on TIME.com

The Hamlet fire / 1991

On September 3, 1991 an industrial fire caused by a failure in a hydraulic line destroyed the Imperial Food Products chicken processing plant in Hamlet, North Carolina. Despite three previous fires in 11 years of operation, the plant had never received a safety inspection. The conflagration killed 25 people and injured 54, many of whom were unable to escape due to locked exits. It was the second deadliest industrial disaster in North Carolina's history. There were 90 workers in the plant at the time. Some were able to escape through the plant's front door, while others could not leave due to locked or obstructed exits. An eerie echo of the conditions that led to 146 deaths in New York City in 1911. Most victims of the Hamlet Fire were women and many were African American. Most were single mothers, leaving over 50 children orphaned.

Mexican Repatriation / 1930's

As unemployment rose to record levels during the Great Depression, Mexican migrants and Mexican Americans were simultaneously blamed for taking jobs from U.S. citizens and, paradoxically, for living off public welfare. In response, immigration officials started deportation campaigns to rid the country of unauthorized migrants, while those who could not be deported because they were legal residents or citizens were pressured to leave “voluntarily.” With the support of the Mexican government, county officials in the United States often sponsored trains to return ethnic Mexicans to the border. The number of repatriated Mexicans is hard to know but estimates range from least 350,000 to as high as 2 million, out of which 60% are believed to have been American citizens—most of them children. However, only a few years after the final episode of repatriation in 1939-40, U.S. officials were desperate to bring Mexican workers back to replace American citizens who had gone to fight in World War II.

CLEARY'S DEN

Love antique, retro, collectables?

There's no better website to shop online for everything out of the ordinary!